Japan’s megabanks are calling time on the yen’s four years of depreciation, a blow to Haruhiko Kuroda’s chances of reviving inflation and growth.

Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd., Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. and Mizuho Bank Ltd. all see the yen ending the year stronger than where it started. And all three have revised up their 2016 forecasts as the yen gained 6.7 percent in the first two months of the year.

The biggest expansion in Japan’s current-account surplus relative to the economy for at least three decades has only boosted the yen’s appeal as a haven from market turmoil. And its advance is not just about investors seeking safety. The lenders point to the waning prospect of a U.S. interest-rate increase, just as the yen becomes less sensitive to Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda’s unprecedented easing. Plus, the yen is the second-most undervalued major currency by a purchasing-power measure.

“Contrasting policy dynamics between Japan and the U.S. are clearly changing this year,” said Daisuke Karakama, the Tokyo-based chief market economist at Mizuho Bank, a unit of the country’s third-biggest lender. “We should go back to the textbook, which says there will be a powerful correction when real exchange rates move out of sync with the long-term average.”

Bigger Bull

Mizuho raised its year-end forecast last month to 108 yen per dollar, from 116 as of September. After ending last year at 120.22 per dollar, the currency reached a 15-month high of 110.99 on Feb. 11 and was at 114.33 as of 6 a.m. in New York Wednesday. It slid more than 30 percent during the past four calendar years, spurred by the BOJ’s stimulus.

A stronger yen is a challenge for Kuroda because it hampers his efforts to kick-start growth and banish the deflation that has blighted the economy since the 1990s.

There’s little to suggest the currency’s gains this year are going to evaporate. Together with the Swiss franc, the yen is the only major currency where options to buy exceed the cost of selling in three months’ time, with a 2.4 percentage-point premium, risk-reversal data compiled by Bloomberg show.

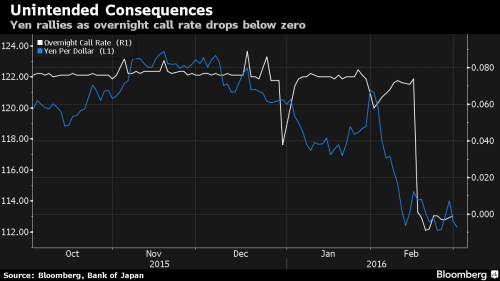

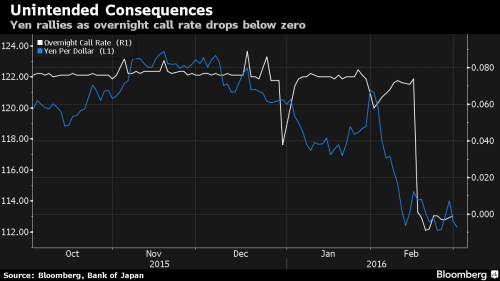

Even the BOJ’s surprise decision late-January to adopt negative interest rates soon led to gains in the yen by making other Japanese assets less attractive. Investors suffered a 9.4 percent drop in the nation’s shares last month, negative yields on their 10-year government bond holdings and the prospect of charges on excess reserves at the central bank.

Policy Limits

“The BOJ’s minus rate revealed the limits of policy, providing a factor that pushed up the yen,” said Shinji Kureda, head of currency trading at Sumitomo Mitsui, a unit of Japan’s second-largest bank. “One has to acknowledge the limited impact of interest-rate policy on currencies.”

Central-bank meetings in Japan and the U.S. in the middle of this month may spur the yen to 105 -- a level last seen in September 2014 -- if it underlines the breakdown in the policy divergence that helped drive the currency lower in recent years, Tokyo-based Kureda said. Yoichiro Yamaguchi, Sumitomo Mitsui’s head of research, raised his year-end forecast to 117 last month, from 123 at the end of December.

The BOJ’s policies have left the yen 29 percent undervalued against the dollar based on consumer purchasing power, the most among 16 leading currencies after Sweden’s krona, data compiled by Bloomberg show. The surplus in the current account, the broadest measure of Japan’s trade, climbed to 3.3 percent of the size of the economy last quarter, recovering from a small shortfall in 2014.

Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd., Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. and Mizuho Bank Ltd. all see the yen ending the year stronger than where it started. And all three have revised up their 2016 forecasts as the yen gained 6.7 percent in the first two months of the year.

The biggest expansion in Japan’s current-account surplus relative to the economy for at least three decades has only boosted the yen’s appeal as a haven from market turmoil. And its advance is not just about investors seeking safety. The lenders point to the waning prospect of a U.S. interest-rate increase, just as the yen becomes less sensitive to Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda’s unprecedented easing. Plus, the yen is the second-most undervalued major currency by a purchasing-power measure.

“Contrasting policy dynamics between Japan and the U.S. are clearly changing this year,” said Daisuke Karakama, the Tokyo-based chief market economist at Mizuho Bank, a unit of the country’s third-biggest lender. “We should go back to the textbook, which says there will be a powerful correction when real exchange rates move out of sync with the long-term average.”

Bigger Bull

Mizuho raised its year-end forecast last month to 108 yen per dollar, from 116 as of September. After ending last year at 120.22 per dollar, the currency reached a 15-month high of 110.99 on Feb. 11 and was at 114.33 as of 6 a.m. in New York Wednesday. It slid more than 30 percent during the past four calendar years, spurred by the BOJ’s stimulus.

A stronger yen is a challenge for Kuroda because it hampers his efforts to kick-start growth and banish the deflation that has blighted the economy since the 1990s.

There’s little to suggest the currency’s gains this year are going to evaporate. Together with the Swiss franc, the yen is the only major currency where options to buy exceed the cost of selling in three months’ time, with a 2.4 percentage-point premium, risk-reversal data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Even the BOJ’s surprise decision late-January to adopt negative interest rates soon led to gains in the yen by making other Japanese assets less attractive. Investors suffered a 9.4 percent drop in the nation’s shares last month, negative yields on their 10-year government bond holdings and the prospect of charges on excess reserves at the central bank.

Policy Limits

“The BOJ’s minus rate revealed the limits of policy, providing a factor that pushed up the yen,” said Shinji Kureda, head of currency trading at Sumitomo Mitsui, a unit of Japan’s second-largest bank. “One has to acknowledge the limited impact of interest-rate policy on currencies.”

Central-bank meetings in Japan and the U.S. in the middle of this month may spur the yen to 105 -- a level last seen in September 2014 -- if it underlines the breakdown in the policy divergence that helped drive the currency lower in recent years, Tokyo-based Kureda said. Yoichiro Yamaguchi, Sumitomo Mitsui’s head of research, raised his year-end forecast to 117 last month, from 123 at the end of December.

The BOJ’s policies have left the yen 29 percent undervalued against the dollar based on consumer purchasing power, the most among 16 leading currencies after Sweden’s krona, data compiled by Bloomberg show. The surplus in the current account, the broadest measure of Japan’s trade, climbed to 3.3 percent of the size of the economy last quarter, recovering from a small shortfall in 2014.